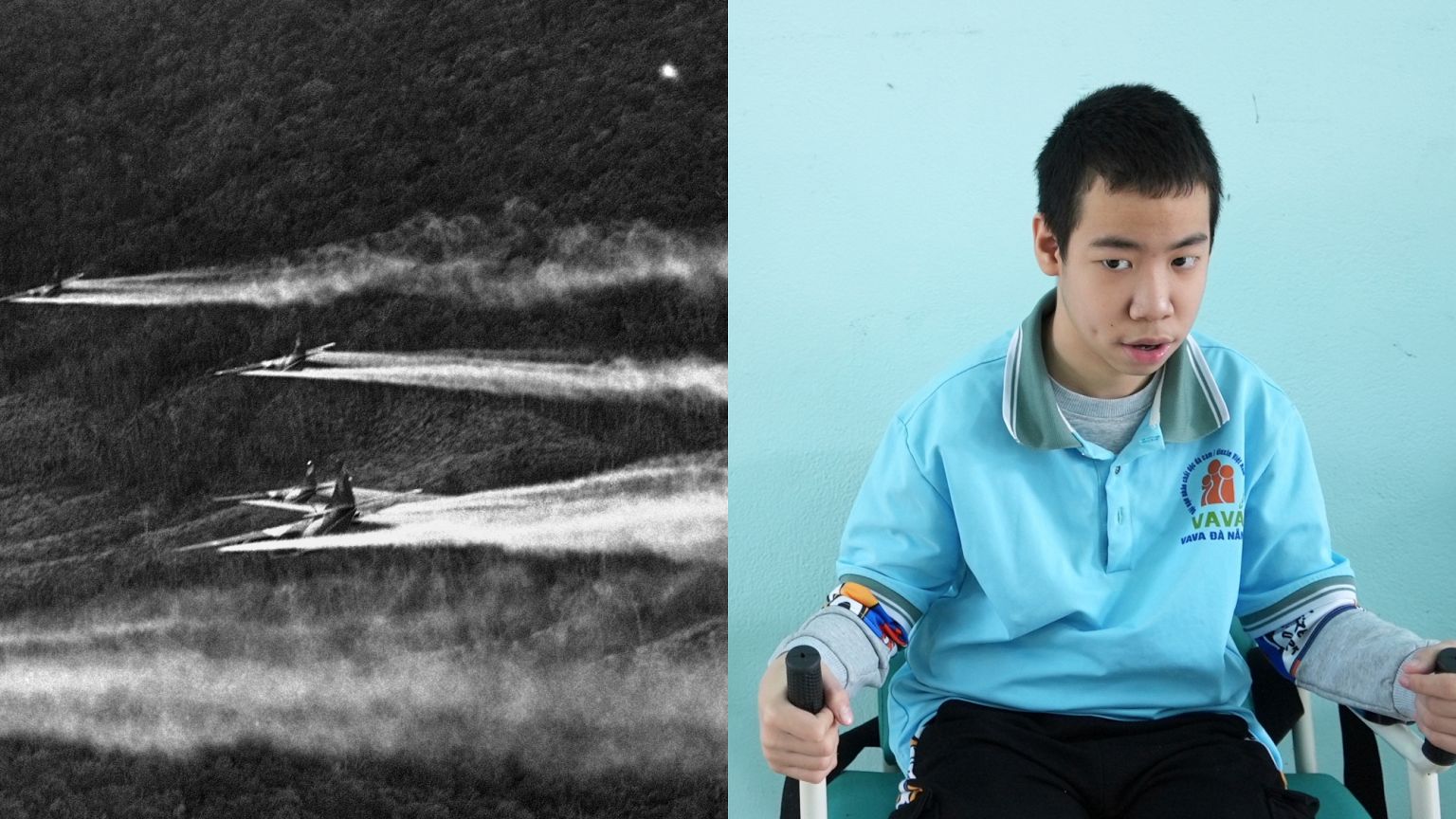

The Vietnam War ended on April 30, 1975, when the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to Communist forces. But millions of people still face daily battles with its chemical legacy. Nguyen Thanh Hai, 34, is one of millions with disabilities linked to Agent Orange.

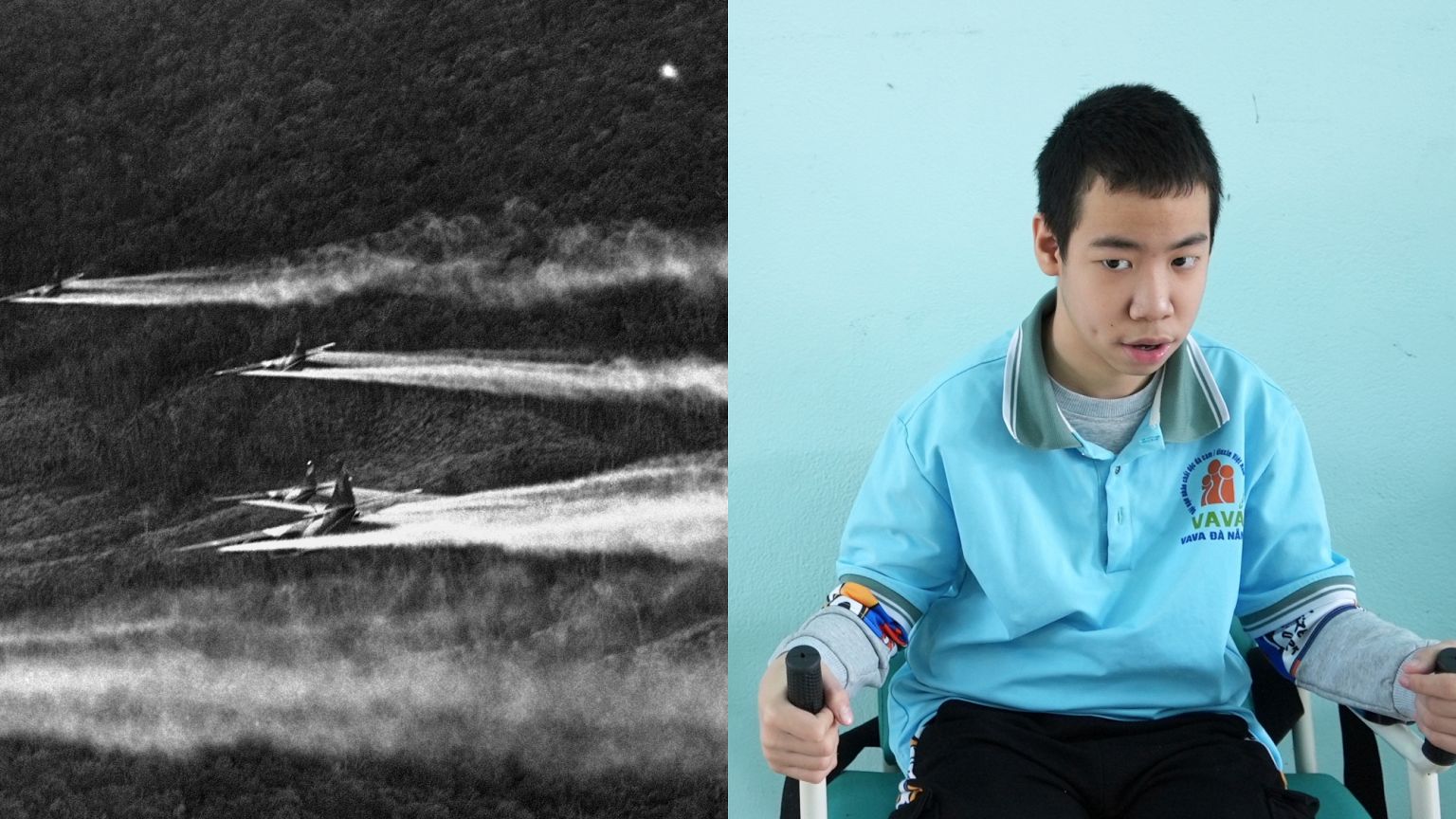

Born with severe developmental challenges, it's a struggle for him to complete tasks others take for granted: buttoning the blue shirt he wears to a special school in Da Nang, practicing the alphabet, drawing shapes, or forming simple sentences. Hai grew up in Da Nang, the site of a US air base where departing troops left behind huge amounts of Agent Orange that have lingered for decades, leaching into food and water supplies in areas like Hai's village and affecting generations of residents. Across Vietnam, US forces sprayed 72 million litres of defoliants during the war to strip the enemy's cover.

More than half was Agent Orange, a blend of herbicides laced with dioxin, a chemical linked to health problems and lasting environmental damage. Today, 3 million people, including many children, still suffer serious health issues associated with exposure to it. Vietnam has spent decades cleaning up the toxic legacy of the war, in part funded by belated US assistance, but the work is far from complete.

Now, millions in Vietnam are worried that the US may abandon Agent Orange clean-up as President Donald Trump slashes foreign aid. When the war ended, the US turned its back on Vietnam, eager to turn the page on a painful chapter in its history. But Vietnam was left with dozens of dioxin hotspots spread across 58 of its 63 provinces.

Vietnam says the health impacts last generations, threatening the children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren of people exposed to the chemicals with health complications ranging from cancer to birth defects that affect the spine and nervous system. But the science about the human health impact, both to those exposed to Agent Orange and the generations that follow, remains unsettled. This is partly because when the two countries finally started working together in 2006, they focused on finding dioxin in the environment and clearing it instead of studying the still-contentious topic of its impact on human health, said Charles Bailey, co-author of the book 'From Enemies to Partners: Vietnam, the US and Agent Orange'.

"The science of causality is still incomplete," said Bailey. In the decades after the war ended, the recovering country fenced off heavily contaminated sites like Da Nang airport and began providing support to impacted families. But the US largely ignored growing evidence of health impacts – including on its own veterans – until the mid-2000s, when it began funding clean-up in Vietnam.

In 1991, the US recognised that certain diseases could be related to exposure to Agent Orange and made veterans who had them eligible for benefits. Since 1991, it has spent over $155 million (€144 million) to aid people with disabilities in areas affected by Agent Orange or littered by unexploded bombs, according to the US State Department. Cleaning up Agent Orange is expensive and often dangerous.

Heavily polluted soil needs to be unearthed and heated in large ovens to very high temperatures, while less contaminated soil can be buried in secure landfills. Large sites still need to be cleared in Vietnam. But Trump’s cuts to US aid funding stalled key projects in Vietnam, and while many have resumed, doubts remain about US reliability.

Vietnam can’t handle the toxic chemicals that still persist without help, said Nguyen Van An, the chairman of Association for Victims of Agent Orange in Danang. "We always believe that the US government and the manufacturers of this toxic chemical must have the responsibility to support the victims," he said. Insufficient data means that experts can't definitely say when the risk to human health will end.

But the more urgent problem is that if clean-up efforts are interrupted, the now-exposed contaminated soil could get into waterways and harm more people. A 10-year project to clear the approximately 500,000 cubic metres of dioxin-contaminated soil – enough to fill 40,000 trucks – at Bien Hoa airbase was launched in 2020. It stopped for a week in March and then restarted, though Bailey, the author, said future US funding for the cleanup was uncertain.

Chuck Searcy, an American Vietnam War veteran who has worked on humanitarian programmes in the country since 1995, said he worries that trust built over years could erode very rapidly. He pointed out that those who benefit from US-funded projects to address war legacies are “innocent victims". "They’ve been victimised twice, once by the war and the consequences that they’ve suffered.

And now by having the rug pulled out from under them," Searcy said..

Health

50 years after the Vietnam War's end, the devastating legacy of Agent Orange remains

April 30 will mark 50 years since the end of the Vietnam War, but the battle with Agent Orange, a chemical used by US forces during the conflict, continues.