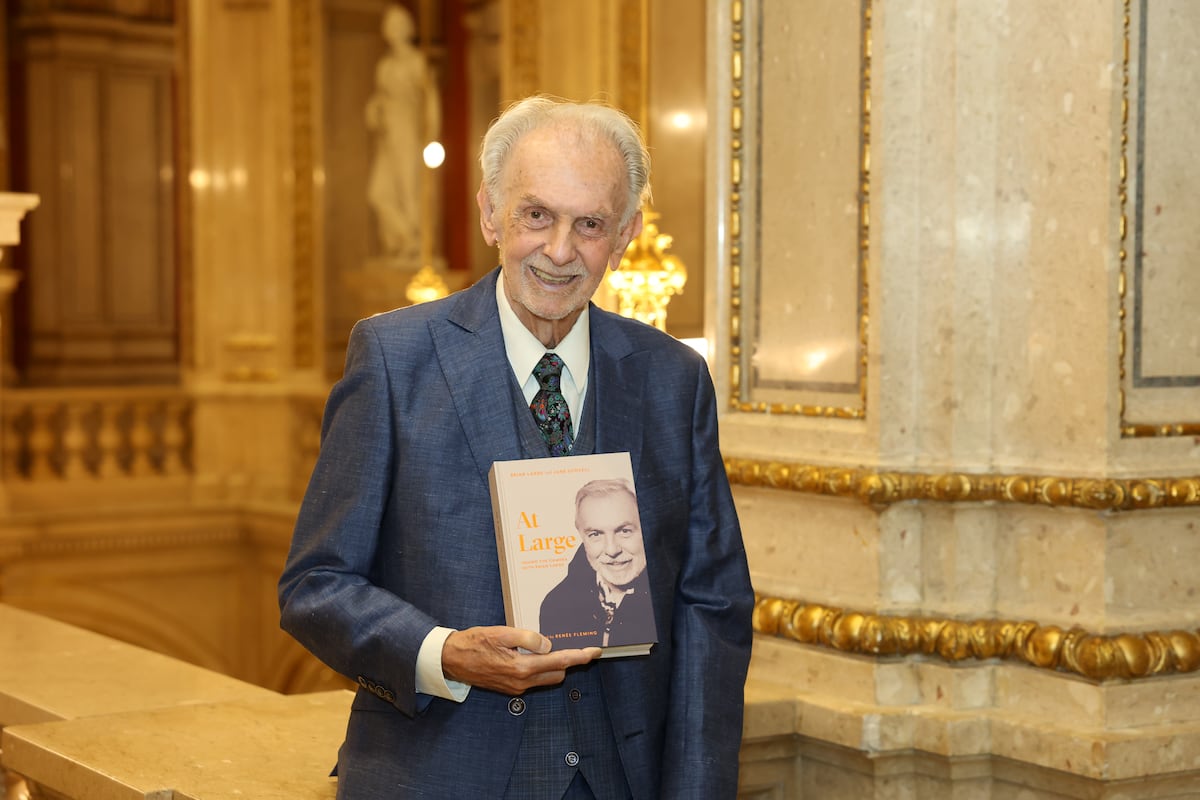

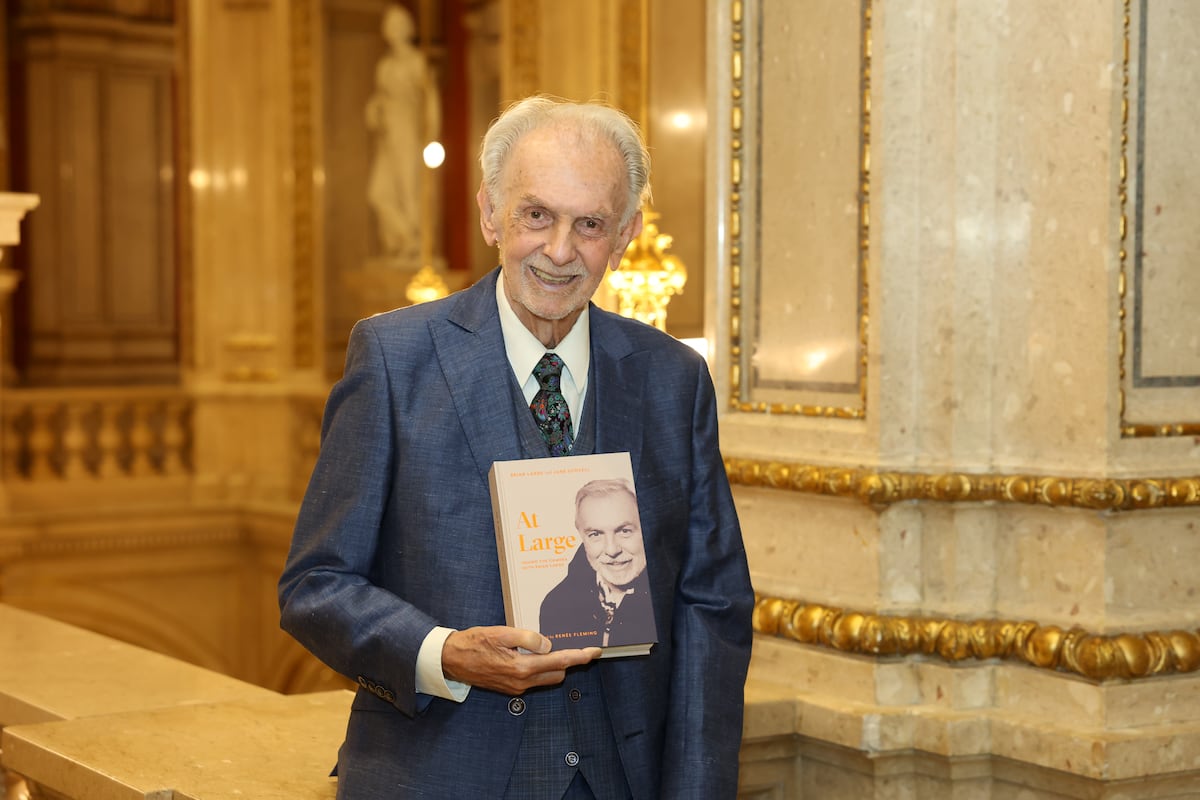

Brian Large, classical music TV director: ‘With The Three Tenors, we created a monster which could not be tamed’ In a new memoir, the man behind so many unforgettable opera and symphonic concerts reviews his relationship with great artists, such as Benjamin Britten, Leonard Bernstein and Luciano Pavarotti You may never have noticed his name, but it’s quite likely you’ve seen a film directed by Brian Large. The 86-year-old is a leading television director and classical music expert, with an immense videography of more than 600 films. This includes numerous audiovisual milestones, such as the first filming of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen , from the Bayreuth Festival — directed by Pierre Boule z and Patrice Chereau between 1979 and 1980 — along with countless operatic productions from the Metropolitan Opera in New York, London’s Covent Garden and the Salzburg Festival.

And, behind the scenes, the London-born gentleman has been responsible for various popular television events, such as most editions of the New Year’s Concert from 1989 until 2011, or the first performance of the Three Tenors, on July 7, 1990, in Rome’s Baths of Caracalla. “We created on that day a monster which could not be tamed,” says Large about the first concert by Luciano Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo and José Carreras . “We had no idea that it would have the success or the impact that it had internationally.

In my defence I only can say I had the best of intentions. Then again, so did Dr Frankenstein,” the continues, smiling, during a video conference from Vienna. The legendary television producer spoke with EL PAÍS after his emotional book launch at the Vienna State Opera on April 1.

His 524-page-long memoir — At Large: Behind the Camera with Brian Large — will be available in August. He wrote it in collaboration with the journalist and playwright Jane Scovell. A voluminous book, it goes beyond a simple personal recollection.

Rather, it stands as a crucial testimony to the audiovisual history of classical music over the last half-century. Large made a difference in the television industry from the start, thanks to his excellent musical training. “My original intention — or that of my parents — was that I would be a professional pianist.

That’s why I trained at the Royal Academy of Music with Myra Hess,” he explains. But making a career as a pianist in the London musical world of the late-1950s wasn’t easy. So, he tried his luck in academia.

“I did a PhD in Music at the University of London and had the idea of writing musical biographies so that I could secure a post in a university to be able to teach music,” he recalls. That project led him to live in the former Czechoslovakia, between 1961 and 1964. This brief period changed his life.

“In Prague, I wrote my two biographies on Bedřich Smetana and Bohuslav Martinů. I even thought about dedicating another to Leoš Janáček, but then I met Václav Kašlík.” This stage and television director opened up a world that Large hadn’t known before.

He learned from Kašlík and his collaborators — such as the visionary set designer, Josef Svoboda — about how to apply cinematic methods to enrich the opera’s narrative. “He took me with him to the Barrandov Film Studios, where he was filming his adaptation of Smetana’s The Bartered Bride . This was followed by Dvořák’s Rusalka .

I was struck by his ability to translate opera into television forms." From 1965, the BBC was his primary training ground as a producer. “I was given the position of director of outside broadcast events, which involved directing soccer, tennis, cricket and horse-racing matches, as well as concerts, opera and ballet,” he says.

That same year, he demonstrated his television expertise in the most famous filming of composer Igor Stravinsky conducting his ballet — The Firebird — at the Royal Festival Hall . “I said, ‘But why me?’ They said, ‘Because you are a musician.’ This allowed me to better capture everything that was happening on stage,” he recalls.

Shortly after, he found the best possible ally at the BBC in John Culshaw. The record producer — who had a successful television career after leaving Decca Records — allowed him to work with Benjamin Britten . And, in 1970, Large collaborated with the composer on the creation of his opera, titled Owen Wingrave .

“I think it was one of the greatest moments of my life. After filming Peter Grimes in 1968 , Culshaw and I persuaded Britten to agree to write an opera for television. He invited me to stay in Aldeburgh for six months to advise him; I went to The Red House [Britten’s iconic residence] almost every day; we had tea together in the library and we worked on technical issues to make his new opera feasible for television,” he recalls.

In his memoir, Large offers portraits of all the classical artists with whom he worked, highlighting their best qualities, as well as their flaws. A good example of this is Britten, whom he describes as a shy and reserved man, who was also resentful and moody. Another example was Leonard Bernstein , whose films with Large — recorded in 1966, while he was conducting the London Symphony Orchestra — helped consolidate his prestige as an orchestra conductor in Europe.

“Lenny was a force of nature,” Large sighs. “He was a dynamite personality. He just breathed music.

I didn’t always agree with his interpretation, but that didn’t matter. I was there as a conduit to be able to record, document and give the public a vision of a man who was a genius.” In the book, he writes about how alcoholism and drugs made Bernstein a difficult artist to work with over time.

Large also mentions his short-lived relationship with Herbert von Karajan, a consequence of the latter’s egocentrism. “I admired him as a performer beyond any degree of imagination. But as a human being, we were not on the same wavelength.

I would dearly have liked to have worked with him, except the position he offered me was not one I felt able to accept. He was offering me to become a technician, someone to press buttons,” Large admits. His memories involving singers are unforgettable.

Large worked closely with all the opera stars, from Birgit Nilsson to René Fleming. In the foreword to the book, Fleming acknowledges her debt to him: he helped her adapt her performance for the screen. Large also helped Nilsson: he knew her trick for keeping her voice hydrated during her performances at the Bayreuth Festival.

Backstage, during a performance of Tristan und Isolde , he saw how she would drink beers hidden in the scenery and — after belching— return to the stage to continue working. Large devised a whole system for her to stay hydrated during the live filming of Elektra in New York: water-filled capsules attached to her dress. She could discreetly tear them off and drink them during the performance.

But no portrait surpasses the one he paints of Pavarotti, both on a psychological and human level. “Luciano was a force of nature, but he wasn’t an easy person to work with. He liked me and we had a harmonious relationship, although he needed to exert his superiority and you had to be very careful because he was temperamentally explosive,” he recalls.

Large directed many of his iconic films, such as La bohème di San Francisco — alongside Mirella Freni — in 1988. “It was difficult to film: His weight was way up and his knees were riddled with arthritis. [Because of this], he didn’t want to move around on stage and protested about everything,” he laments.

In the book, Large explains how he knew how to limit Pavarotti’s eccentricities, such as when the singer demanded to reshoot a scene after the crew had already disassembled the set. The producer would pretend to have convinced the crew to do it again..

. but would also inform Pavarotti that the tenor would have to pay for the reshoot. “Punching him in the money belt was a low blow but absolutely necessary.

” Perhaps Large’s most prestigious filming was the aforementioned Wagner tetralogy, at the Bayreuth Festival. “It was an exciting project. [I couldn’t think] of a more ideal place to film it for the first time than the theater where it premiered in 1876.

With Boulez, it was very easy: we had worked together when he conducted the BBC Symphony Orchestra, we were friends. The relationship with Chéreau was different; personally, I was fascinated by his stage concept for Der Ring des Nibelungen , even though he knew nothing about television,” he notes. Large explains how he managed to attract the French stage director’s interest and how he began correcting the movements of famous singers — like Gwyneth Jones and Donald MacIntyre — while looking at the television monitor.

Large’s filming style — maintaining the utmost respect for the conductor’s intentions — set a standard for broadcasts of the Vienna Philharmonic’s New Year’s Concert. The first broadcast he conducted was in 1989, with the debut of Carlos Kleiber, perhaps the best edition in history. “Carlos was a genius, but he was always nervous.

Nervous that he couldn’t get the results he wanted. It was his nature. And he was able to achieve that quality from the orchestra, thanks to his charm and persistence.

But he was very temperamental and could be extremely rude.” “[Carlos] loved the work of Riccardo Muti. They were very close friends.

And I remember, before the first New Year’s Day concert, Muti was calling him, wishing him good luck [and assuring him] that ‘Brian will look after you. You’re in good hands.’ Afterwards, I remember Kleiber received another call from Muti, congratulating him.

It was a very harmonious thing.” Large also recalls Kleiber’s misgivings about Lorin Maazel. He experienced this during a 1996 broadcast of Tristan und Isolde at the Prince Regent Theater, in Munich.

“Carlos secretly asked to join me, so that he could watch the performance from behind me in the broadcast booth. I felt like the filling of a sandwich between two great conductors. But his breathing became increasingly noisy during the first act.

He left during the intermission, angry at Maazel’s slow style,” says Large. Large’s memoir begins with the Blitz: Nazi Germany’s bombing campaign against London during World War II. The family home was lost in the bombings and Large — like the protagonist of Steve McQueen’s latest film, Blitz (2024) — became one of the many children who were evacuated to the countryside.

The producer worries that younger generations have forgotten the barbarity of that war. “I pray to God every day that there won’t be a Third World War,” he repeats several times during his interview. “I’ve always maintained that one of the greatest things music can do is to bring harmony and peace and respect for human life.

And I hope every concert I did, every piece of music I did, was with that intention of being able to make people feel happy, at peace, content with the world and grateful to be able to live on this wonderful planet,” he concludes. Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo ¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción? Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro. ¿Por qué estás viendo esto? Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS. ¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí. Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.

Plácido Domingo José Carreras BBC Benjamin Britten Leonard Bernstein Herbert von Karajan Brian Large, classical music TV director: ‘With The Three Tenors, we created a monster which could not be tamed’ Rich, tacky and proud: The ‘boom boom’ trend that always emerges during crises Fracking: The fuse for Trump’s trade war Liv Tyler’s return: The actress who prefers ironing sheets in the countryside to being crushed by Hollywood The corrupt Pope who sold his office for money and forced the Church to create the conclave NASA astronaut Kathryn Thornton: ‘All the progress we’ve made over the past 70 years is in peril’ Who’s who in the conclave: The 133 cardinals who will elect the new pope Son of a CIA deputy director fought and died in Ukraine as a Russian soldier Traditionalists who tried to overthrow Pope Francis wait for their moment at the conclave.

Top

Brian Large, classical music TV director: ‘With The Three Tenors, we created a monster which could not be tamed’

In a new memoir, the man behind so many unforgettable opera and symphonic concerts reviews his relationship with great artists, such as Benjamin Britten, Leonard Bernstein and Luciano Pavarotti