I f ordinary and familiar products like chairs, tables, bread, books, etc, are assigned masculine and feminine articles in languages such as Urdu, Persian, Arabic, French, Spanish and German (but not in English, Finnish or Hungarian), some supreme and grand entities are also referred to using male and female genders. To the followers of the three Semitic religions – and some other faiths – God is male, whereas in most parts of the world, the Earth is described as female. The term Mother Earth often appears in political rhetoric, patriotic propaganda, popular cinema and vernacular imagery.

Subsequently, a large number of terracotta or stone figurines found at ancient sites were classified as mother goddesses. Similar statues excavated from Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, and other locations of the Indus Valley Civilisation, have influenced several artists in Pakistan, including Nausheen Saeed. In the catalogue for her exhibition Enigma (17 April–16 May, White Gallery, Lahore), she explains: “Inspired by the ancient heritage of the Indus Valley Civilisation, I find myself drawn to the strength of the feminine forms that emerge from its relics.

” Compared to other female artists who stylise historic findings in their prints, paintings and sculptures, Saeed investigates ancient objects not for formal or sentimental reasons. Intriguingly, in her statement, she uses the word relics instead of figures or sculptures. The same approach is evident in the five artworks on display at her solo show.

Alongside the terracotta mother goddesses, earthenware has also been discovered in various settlements of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Nausheen Saeed draws a connection between these two types of artefacts – primarily through their shared material, clay, but also through their content and function. A clay pot is used to store water, milk or grain – essentials for human survival.

Its ingredients are sourced from the earth and, once broken, it returns to its origin, merging with the soil, only to be reshaped into a new clay form, often circular when thrown on a traditional potter’s wheel. These are characteristics our ancient ancestors likely recognised in a woman, especially in a mother. She carries a child in her womb, gives birth and sustains the newborn by feeding it her milk.

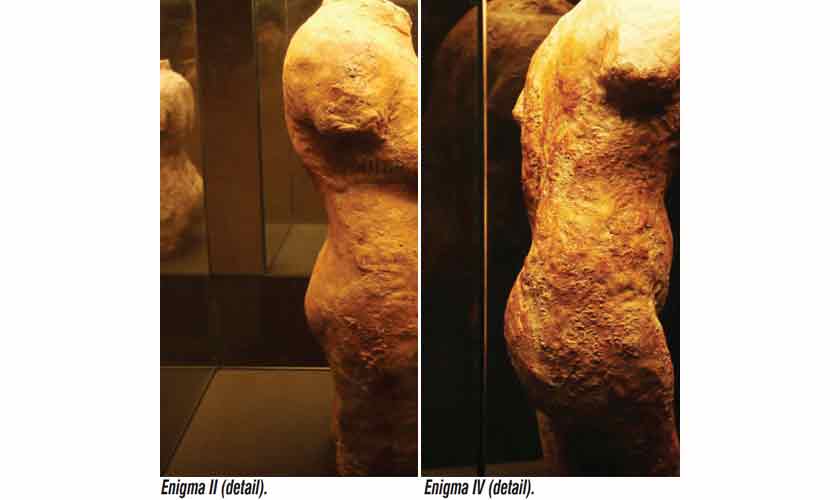

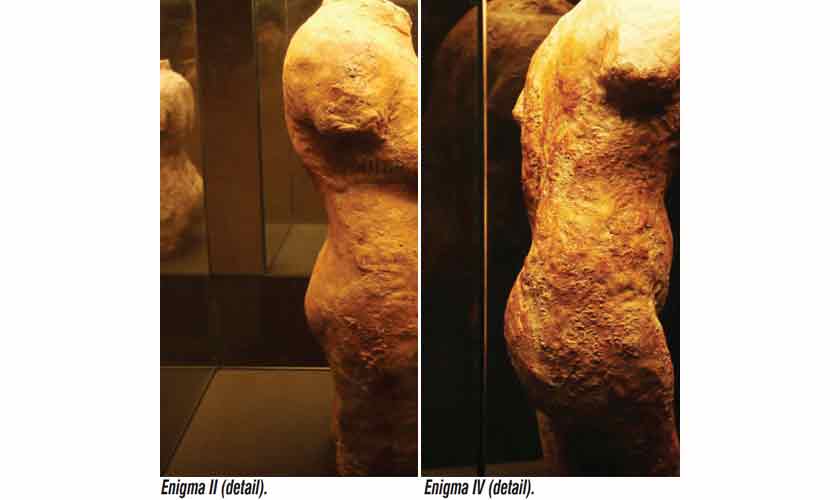

Unlike a man, her body is rounded rather than angular, particularly during pregnancy; and after death, she is buried in the ground, cremated or lowered into water – only to be resurrected in the features and form of her offspring. The connection between a mother and a terracotta pitcher is suggested in Saeed’s work through her treatment of the surfaces of female forms as if they were produced in fired clay. This impression is reinforced by the colour, texture and roughness of the body – earthen qualities often associated with women of a certain age and melanin, maternal figures from our surroundings (in a region where the prevailing idea of beauty is tied to ridding the skin of its natural hue, often perceived as dirt, using all manner of scrubs, whitening creams and bleaching agents; even clinical procedures.

) In stark contrast, Nausheen Saeed’s sculptures, through their striking presence, reclaim the awe of being a dusky woman. They honour a body that is not a model of prettiness or a testing ground for beauty products, but one that holds a significant, larger and lasting role. Though the artist never claims to be a feminist, akin to Margaret Atwood (author of the essay Am I a Bad Feminist? 2018), she is acutely aware of the plight and power of women.

In her statement, she reflects: “The entity we call ‘woman’ often remains undefined, to the world, and at times, even to herself.” In her art, she honours “this mystery” and salutes “the strength, grace, transformation and resilience of women across time.” The resilience of an ancient terracotta jar, having survived for centuries, becomes a symbol for women of the Twenty-first Century, who must endure all kinds of abuse, cruelty, pressures and oppression: physical, psychological, economic, religious, cultural, social, amorous and domestic.

There are no barriers of age, background, appearance, dress or profession; even life and death. Cases have been reported of mentally disturbed individuals attempting to desecrate the bodies of recently buried women. The entity we call ‘woman’ often remains undefined, to the world, and at times, even to herself .

Saeed has not only transformed the outer skin of women in her sculptures, but also introduced an attribute that dominates every man – whether politician, judge, general, CEO or athlete – for all of them once resided inside the body of a woman who brought them into the world, fed them, and cared for them, until they, tragically, acquired the power to subjugate women. In Saeed’s sculptures, this aspect of womanhood is strikingly present. The figures, missing heads and limbs, resemble mothers more than the famed Second-Century BCE Greek sculpture Venus de Milo , long hailed as a symbol of perfect beauty.

With their external surfaces layered in lines, marks, hand impressions, bruises, cuts, crevices, scratches and spots, these sculptures represent women who have endured the full force of lived experience: childbearing, surgeries, labour, physical exploitation and aggression. They carry these in their memories – and within their bodies. It is not the first time Nausheen Saeed has transformed the body of a woman, primarily into a container.

In the past, female figures have been fabricated from freshly baked bread, morphed into masses of soap, assembled from discarded cloth cuttings and constructed with roses, indicating qualities ranging from delicate to attractive to nourishing. The element of nourishment was explored in her metal pieces: partly female torsos, partly steel cans (manufactured for storing and transporting milk). Translating delicate flesh into a hard substance, on the one hand, points to the suffering of women in society; on the other, it demonstrates their strength and endurance.

Two earlier groups of work – both different kinds of containers – allude to the existence or presence of a woman. In one, females are converted into luggage pieces, which are typically stuffed with inseparable belongings before embarking on a journey. A collection of personal possessions that undergoes scrutiny at every point of departure and port of arrival (an operation not dissimilar to a woman’s regular exposure to the male gaze in public spaces).

By coating baggage/ women with printed fabric, Saeed created a parallel between a female and her sculpture, as both are subject to detailed scrutiny. All hidden contents are examined by outsiders. The other series of containers resembles humanoid plastic shoppers – empty, yet swollen, as if still holding groceries.

They communicate that a male-dominated society perceives females as functional beings: to bear children, to maintain the household and to provide pleasure. Once these roles are fulfilled, they may be seen as dysfunctional, if not discarded altogether. However, Saeed, by switching the soft, malleable and wobbly materials of the initial forms into stiff and strong layers of resin, conveys a woman’s endurance in all – even unfavourable – circumstances.

Saeed’s new work from her current exhibition, Enigma , is a continuation of her previous concerns. These women/ earthenware represent a section of the body that encompasses vital organs such as lungs, heart, stomach, liver, kidneys, intestines, and, in the case of an expecting mother, another life. Thus, women are not far removed from jars – a connection made most convincing by a small detail: the head of each torso resembles the opening of a clay pitcher, designed to be filled with liquid or solid.

In addition to merging both forms, Saeed stitches together two time periods. Her current sculptures, due to their pictorial and technical resolutions, resemble historical artefacts – a reading reinforced by their display in an anthropology museum-like layout and lighting – and are a culmination of her earlier artworks, especially the body casts she created after graduating from the National College of Arts. An important aspect of the aesthetics of Nausheen Saeed (the first Pakistani to acquire an MA in Site-Specific Installation from the UK) is that the work does not consist merely of bodies – their external finish, their neutral pedestals, their glass boxes, their glimmering with a faint luminescence, the dark and almost receding walls of the gallery – but of all of these elements together.

Through these quiet, sombre and serene settings, Saeed appears like Cézanne, who wanted to “make of Impressionism something solid and durable like the art of the museums.” The writer is a visual artist, an art critic, a curator and a professor at the School of Visual Arts and Design, Beaconhouse National University, Lahore. He may be reached at quddusmirza@gmail.

com.

Entertainment

Context as content

I f ordinary and familiar products like chairs, tables, bread, books, etc, are assigned masculine and feminine articles in languages such as Urdu, Persian, Arabic, French, Spanish and German , some supreme and grand entities are also referred to using male and female genders. To the...