Inflation takes center stage in investment discussions in 2025, as many countries see strong tariffs accompanied by inevitable high price increases. In Nepal, the annual inflation rate declined slightly to 5.4% in January 2025.

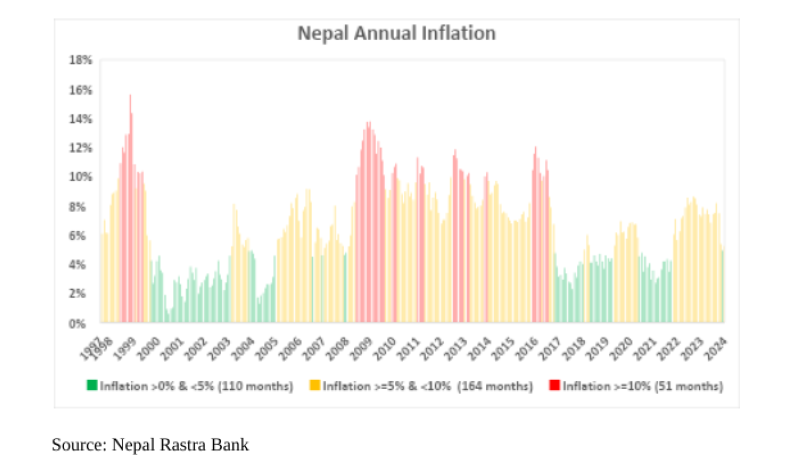

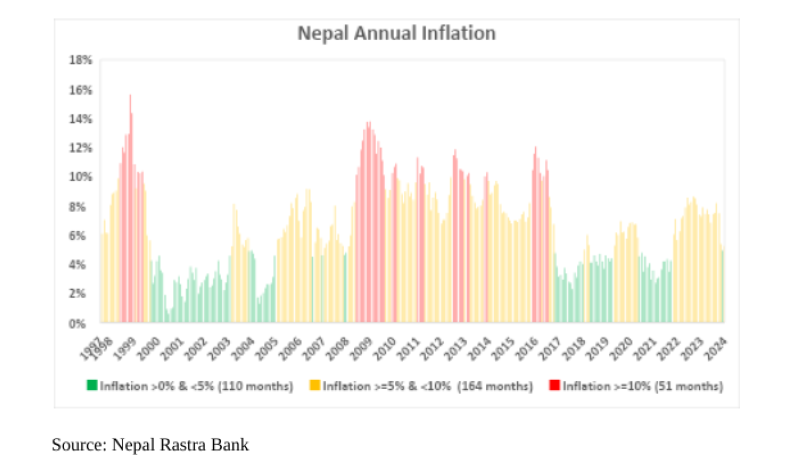

Inflation has long been a central concern for investors, but its significance has grown markedly since Nepal Rastra Bank adopted prudent stance by retaining its current policies, prioritizing stability over bold reforms. While inflation has generally declined since 2020, the large-scale expansion of the money supply has fueled concerns among inflation hawks. Between 1997 to 2024, the average annual inflation rate in the Nepal was 7.

8%. Inflation exceeded 10% just 16% of the time. Most commonly, inflation ranged from 0% to 5%, occurring 34% of the time, while it stayed between 5% and 10% for about 50% of the period.

In today's markets, most investors know high inflation more from historical accounts than personal experience. While it's a frequent topic of discussion, only a few traders have directly encountered the serious disruptions it can cause to economies and financial systems. I defined three distinct inflation regimes for the period from 1997 to 2024, utilizing inflation data sourced from the Nepal Rastra Bank and stock market data obtained from the Nepal Stock Exchange.

Average monthly equity returns were similar across various economic conditions. The weakest returns were observed during high inflation periods, which often align with purchasing power of money. Interestingly, inflation rates exceeding 10% did not appear to adversely affect stock market performance.

Failing to adjust for inflation is a common oversight when analyzing investment returns. For instance, a savings account earning 5.3% interest might seem worthwhile when inflation is at 3%, but that return turns negative in real terms if inflation rises to 6%.

When comparing nominal and real monthly equity returns across three different inflation environments, the picture changes significantly. In real terms, inflation above 10% notably diminished returns, and when inflation exceeded 0%, equities became largely unattractive. While it's possible that real returns remained negative indicating that equities don't provide some inflation protection stocks are inherently volatile.

Relying on average returns can be misleading, as it obscures the severe drawdowns experienced over the 30-year period. During periods of high inflation specifically when it surpassed 0% my review of 9 sectors from the Nepal Stock Exchange revealed that the most impacted industries were those tied to consumer, such as mutual funds, microfinance, and life insurance. Having the inability to adjust interest rates, these sectors often struggle to fully pass rising inflation to the consumers.

Low inflation can negatively affect mutual funds, microfinance, and life insurance. In mutual funds, especially those with significant fixed-income investments, low inflation typically results in lower yields, reducing overall returns. For microfinance, lower inflation can diminish the real value of loans, potentially leading to decreased repayment rates.

In life insurance, low inflation can erode the purchasing power of death benefits and may increase lapse rates, as individuals have less incentive to save for the long term. Sector performance was not uniform when inflation ranged above 10%, with some sectors even delivering positive returns. In contrast, the sectors that benefited most from high inflation were consistently the same during both periods of elevated inflation: manufacturing and banking which are commonly favored by investors when adjusting equity portfolios for inflationary conditions.

The sectors most positively impacted were those engaging directly with consumers particularly in manufacturing and processing. Owing to their pricing flexibility, these businesses were generally able to successfully transfer rising costs to their customers. Amid periods of heightened inflation, the Manufacturing and Banking sectors distinguished themselves by delivering the most substantial dividend payouts.

A recent example is the way US companies are passing increased costs onto consumers. Leading US firms remain confident in their ability to maintain record profit margins by transferring rising expenses to customers, supported by strong business activity and positive consumer sentiment despite inflationary pressures. While this supports the idea that traditional assets can hedge against inflation, there are important caveats.

The two major high-inflation periods in the last decade mainly took place in 2015, when Nepal's inflation peaked at 12.06%. This surge was largely driven by a Nepal's earthquake following Nepal's blockade.

The prices of iron, steel, and cement products surged due to increased demand for construction materials driven by reconstruction efforts. While some equity sectors have shown characteristics that could hedge against inflation, this information isn't practically useful without market-timing expertise. Additionally, these stocks often act as proxies for financial service sector, meaning that even if investors could predict inflation, they might be better off directly investing in direct manufacturing and banking exposure might be a better strategy.

A potentially more intriguing inflation hedge could be investing in trend-following, manufacturing and banking focused funds. These funds can capitalize on rising oil or gold prices when inflation increases, jumping on the trend as it develops. While this strategy isn't foolproof as the past decade has shown it could offer a more sophisticated way to hedge against inflation.

.

Politics

Debunking the Myth: Stocks Protect Against Inflation

Inflation takes center stage in investment discussions in 2025, as many countries see strong tariffs accompanied by inevitable high price increases. In Nepal, the annual inflation...