“Truman Capote, an Interview,” by Cathleen Medwick, was originally published in the December 1979 issue of Vogue. For more of the best from Vogue’ s archive, sign up for our Nostalgia newsletter here . Truman Capote knows how to make an entrance.

He has always known. In 1948, when he published his first book—a slim siren of a novel called Other Voices, Other Rooms —he quite simply created a sensation. It was not just the lush beauty of his prose, his precocious mastery.

It was also that the book's jacket displayed a photograph of the unknown young author: a delicately pale young man reclining on a chaise lounge, his eyes leveled provocatively at the camera. They were the eyes of a lover, or a murderer. A tough faun, as a friend has said.

Truman Capote at twenty-three was the New Orleans country boy who came to the big city and, with cool country know-how, seduced it. That was an artful seduction: as though Truman, a boy fishing at an enormous pond, spotted a great, elusive fish and knew just how to get it: camouflaged his hook with gleaming bait (himself) and waited with the patience of saints. When he caught that fish, fame, he caught it suddenly, and for keeps.

His talent, was, of course, the hook. Without that, he could never have joined the front ranks of contemporary Southern writers—Porter, Welty, McCullers— and stayed there, as one of America's foremost literary talents, for over thirty years. Since the boy on the book jacket, we have seen many Capotes.

Like a wizard, he is always assuming new shapes, new disguises. A small, dapper Capote in a grey pinstripe suit and black-rimmed glasses, leading a gelatinous Marilyn Monroe in a dance at El Morocco in 1954. A beaming, black-tie Capote in a black mask (Capote the social butterfly), the darling of the jet set, ushering newspaper heiress Katharine Graham into the $75,000 ball he threw for her in 1966—threw it, he said then, in order to go to a party where he could really have a good time.

A thinner, dowdier Capote (one of his friends said that his pants always looked baggy, like he'd been whacked in the ass with a shovel) being frisked at San Quentin, where he was interviewing murderers in 1972—several years after his mercilessly detailed account of a Kansas murder, In Cold Blood , established him as a major force in American writing (Capote the serious author). A plump, porcine Capote wearing shades and playing in the 1976 movie Murder by Death (Capote the movie star). A betrayed and belligerent Capote, after chapters from his still forthcoming book Answered Prayers , a thinly disguised tale about his jet-set friends, were published in Esquire , and the Beautiful People closed their doors on him.

Finally (it seemed then), a down-and-out Capote confessing his addictions to drugs and drink on the Stanley Siegel talk show, and expressing quivery intentions of overcoming his addictions—if he didn't accidentally kill himself first. These were the images the press eagerly fed the public over the years. Or, rather, the images that Capote fed the press.

But no matter how many masks he assumed, how much each new Capote shocked and titillated the public, there was always a backbone of achievement that made Capote more than fodder for gossip columnists, or his erstwhile friends. There was always a new work, and it was always good. Capote's writing, like his public image, seemed capable of endless transformations.

Out of the haunting prose-style of The Grass Harp and the early stories he distilled a new literary genre—a kind of reporting that revealed reality to be even more freakish, more fabulous than fiction. In Cold Blood was (like its author) vivid, shocking, and impossible to ignore. As Capote's own life became more of a fable than ever, as the "tiny terror" sharpened his claws on Gore Vidal and other opponents, as his social status plummeted, the public's appetite for Capote's prose became even keener.

Today, more than ten years after it was first promised to them, prospective readers of Answered Prayers are still licking their chops with anticipation. Fame and notoriety have always mirrored each other in Capote's life, and still do, like the Siamese twins he uses nowadays as his literary personae: Capote, meet Capote. Janus faces, the killer and the saint.

To his enemies, Capote is, almost literally, the spitting image of the person they have attacked: he can caricature himself better than they can and, in so doing, become a kind of avenging demon. To his friends (and his lovers), Truman is a childhood fantasy—a Dutch uncle, a bosom companion. These are also masks, mirror-images; but they are not lies.

Inside the fiction hides the truth. Inside the mask, another mask. There is a Truman Capote that few people have ever seen: the artist who is continually taking the measure of himself and his work.

Talking about his career, Capote assesses himself minutely, as a saint would do; he details, with an objectivity that can be chilling, the progress he has made toward his goal. "It has nothing to do with ego. It certainly doesn't in my case because I honestly don't have very much ego.

I have a tremendous feeling about the importance of my writing. I mean, I owe it to God, if you want to put it that way, to achieve what I know I can. I can't stop here, you know, because there is this other level, the ultimate state of grace—and I have to get there .

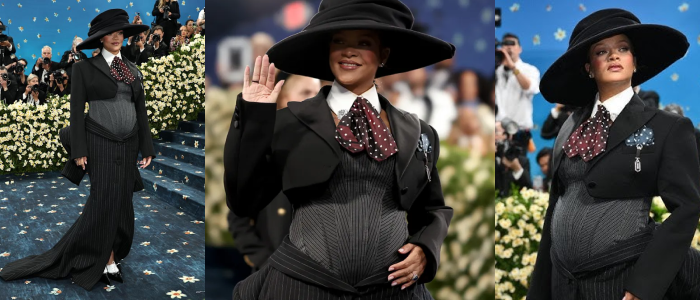

" The Truman Capote who speaks is, at fifty-five, a wisp of a man—only ninety-three pounds—wearing, nevertheless, a big, flamboyant straw hat ("Do you like my hat?" is what he asks as he makes his entrance into the room). In fact, the hat makes his face look longer, paler, a kind of underlying apparition. But the eyes are burning bright—the eyes of someone who has seen and fought demons, is still seeing and fighting them.

As if to flick the demons out of sight, Truman finds things to entice him in far corners. He drifts—is wafted—into a chair; but, instead of resting in it, he seems to be buffeted by some mean, childish wind that ruffles the loose skin on his neck and makes his hands float in the air, his body flutter. He is like some angular bird that might, at any moment, fly out of the room and escape into the noon sky.

When he talks, it seems at first as if his voice, too, is weightless—that mewing whine of his, but fading or (his kind of word) perishing. Until he speaks about himself, his reputation: then his voice concentrates into a glassy, sharp-edged ping; he flies at you, even pounds his fist on the table, wanting you to know about him, who (he says) he really is. "I consider that I have a career as an artist.

I'm fifty-five years old and I've been writing professionally for almost forty years. That's a very long time. Most people—you know, famous people, personalities, usually they're entertainers—have very short careers.

A writer can have a long career, but very few of them actually do. Because it's so nerve-shattering. It's this continuous, constant gamble.

I mean, if you're really a good artist. If you're not a good artist, well, it doesn't matter, because your conscience isn't affected. You're not continuously striving and reaching and being miserable and happy and taking drugs and drinking and doing something to try to get out of this ghastly tension.

Because what you're doing is gambling with your life" (a strident ping here). "It isn't reputation, this is your life, these are the years gone by, and am I wasting them? Have I totally wasted it? " Capote is leaning forward now, his eyes shooting blue lasers as he speaks, his fist pounding the table, punctuating his words. "I mean, I think I have a really great gift, and I owe it somehow to get it out ! But I have to get it out the best possible way, and that is what makes an artist have a career: it is this integrity of holding on, holding on, holding on no matter what.

" Like Proust, when he shocked the elite of Paris by publishing their secrets, in Remembrance of Things Past ? "Well, Proust really had a relatively short career. It was monumental, but it was short. And when he first began to publish his books, he was not a famous writer.

So when he was attacked, he was attacked in a very limited circle by people who knew him. But the big difference is that when I started to publish I was a very famous writer. And person, period.

The attack on me was monumental! I mean, from all sides—you'd think I'd killed Lindbergh's baby! That it wasn't Hauptmann at all, no, it was Truman Capote who had stolen the child and strangled him." Capote is in his element now. In control of his tale.

"And they didn't let it go at that. I mean, everything in my personal life, you know. So, I had an alcoholic problem.

Well, my God, they turned that into the war of the worlds or something. I survived it. I overcame it.

It was a tremendous struggle, but God knows nobody was helping me. I mean, I thought it was a very small reward for having devoted so much of your life to contributing, you know..

.But that's how things go. They build you up and they knock you down.

Build you up and they knock you down." Why, in Capote's mind, do people turn against him? "It's a kind of human nature thing, I suppose. It happens to everybody.

It happens to everybody who has a career that lasts long enough, I can assure you. At some point they're going to turn against you. I mean, I've been turned against several times.

When my first book came out, Other Voices, Other Rooms , I was overnight an incredibly notorious person. Well, I would call it turning against me, wanting to destroy the book and the reputation I achieved by attacking my personal character." Superimposed: the image of the sultry, smoky-eyed young man, challenging from his chaise lounge.

.. "Well, the photograph was simply an image of something else they wanted to attack.

They wanted to attack my entire nerve, the gall of me to be what I was." And when people attack him that way, does he think they really want him to go on being what he is? "Basically, they do..

.I no longer pay any attention to any kind of an attack at all. Believe me, I don't.

They can accuse me of mass murder and it wouldn't make my pulse skip a beat. I don't care about anything, I..

.but what was the question?" Does he think people..

. "I think," (his voice like a schoolmarm's, like a ruler rapping the knuckles) "that if you back down from something when you're attacked, they will then scent fear and blood and come after you, wham. And I knew that full well and so I never backed down.

Well, I didn't feel like backing down. Why should I? I was right! I was doing the right thing! They were wrong! They were stupid! And so, I wouldn't back down, I didn't back down, that's what you should do. "Just go on doing what you're doing.

And even if it's wrong, go on doing it. You shouldn't ever let them sense a weakness in you, because then they'll go for you like sharks go for somebody with his blood in the water." In a world of predators, it is either eat or be eaten.

And an artist faces one more danger, that he will consume himself. "It's really totally incredible the state of tension that a person like me lives in. And most people don't realize it.

First of all, I am receiving about fifteen more impressions per minute than most people. You know, that's a big strain in itself." Truman receives impressions as if they were telegrams, secrets that no one else knows.

Like the way a lizard moves, liquidly, and the way it turns a dreamily disturbing color under water. The way a cottonmouth rears up, winding, hypnotizing with its eyes, until there is no place to run. "And people say, well, why do so many painters and writers drink, why do they take drugs? Well, I understand it perfectly, because I went that route.

I got out of it because if I hadn't got out of it I would have eventually killed myself." Does he ever feel he is working against time? "Yes, that phrase has crossed my mind, but I don't feel it in the sense that Proust felt it, since he was dying. I feel that I have to achieve a certain thing by a certain time in order to relax enough to go on to the ultimate fulfillment of my gift.

I feel that I have to, within a year, have achieved something in my new phase that will give me a certain sense of relaxation and confidence so that I can catch my breath before, you know, taking that tremendous leap." He writes now for many hours at a stretch, in a room he has acquired just for the purpose. The room is all white, with just some photos taped to the walls.

A view of the river. Truman writes standing up, facing the view. “For the last year or so, I really have been doing nothing but work work work work work.

I work at writing ten, eleven hours a day. I mean, I've never done that in my life. And I know it's going to go on that way.

I long for some sort of break in the thing, an end to it...

” He says he does not go out anymore—except to the gym, where "I go swim in the damn pool every day for an hour and I hate it; it bores me out of my mind. And I don't want to eat, because I have a mild anorexia, I don't know why. But I force myself to eat just because I've got to stay in top condition.

" There is this feeling he has, really always has had in public, that he is there but not there. Recently, he had to leave a Broadway show in the middle because he couldn't concentrate. And he has come to hate going out for lunch or dinner because, frankly, it makes him extremely nervous.

"I have a distinct feeling that my whole life has been, since I was seventeen years old—that I've been living inside an electric light bulb, and that it's all a play. People come in and take various parts in the play, and then they depart and they come back, or they sit down, but it's like a continuous, ongoing play with a large audience watching it. "Somebody asked me about a year ago, what am I famous for, and I said 'I'm famous for being famous.

' You know? That's one way people can be destroyed. I've always been famous for being famous; but, at the same time, I was aware of it. So therefore it didn't affect me, and it wasn't the poisonous thing that it is.

It's a subtle kind of poison, and people don't realize when it starts." When the cottonmouth is poised to strike, Capote does something. He writes.

So that always, however venomous the attack, there is a substance that is indestructible, a body of work. Writing is Capote's most potent kind of wizardry, his antidote for snakebite. With it, he can charm the beast and protect the most vital part of his own being.

That is how Truman Capote has survived—drugs, alcohol, serious physical illness, betrayal by friends—and that is why his literary reputation is his life's blood. His survival is, as he readily admits, a miracle. Still, it was no surprise to see his gremlin face grinning from the pages of Interview this past year, with the running question "Is Truman Human?" (Not even Interview dared to answer that.

) It is no surprise that Esquire , which heralded his fall from grace with tidbits from Answered Prayers , is publishing this month a new piece called "Dazzle." A miraculous kind of comeback—but Truman never really went away. He is a fighter, after all, red in tooth and claw—and perhaps it is just that killer instinct that saves him.

.

Entertainment

From the Archives: An Honest Interview with Truman Capote

Truman Capote knows how to make an entrance.