Washington loves a leaker — an “unidentified source” who’s willing to spill the beans and dish on his boss or colleagues. Sometimes, the motivation is revenge, settling the score for an old wrong, be it real or imagined. Other do so for reasons of conscience, believing the public needs to know what’s happening behind the scenes.

It brings to mind one unidentified official who long ago disagreed with his boss. And what he did to inform Americans about it played a big part in the buildup to the Revolutionary War. This is the story of the Hutchinson letters affair.

Britain had an increasingly nasty problem on its hands in the early 1770s. For nearly 150 years, the mother country and its Provinces of Massachusetts Bay colony had enjoyed more-or-less tranquil relations. However, things had recently soured.

The colonists said it was grossly unfair that a heavy round of taxes was imposed on them for London’s fiscal benefit, not theirs. Despite paying those taxes, the people of Massachusetts had no voice in Britain’s Parliament, and they were growing increasingly upset about it. That, in turn, upset the Brits, who felt the colonists were acting like spoiled, ungrateful children.

The tipping point came in 1773, when the infamous Tea Act was passed. It was the last straw for many of Massachusetts’ tea-sipping British subjects. And that’s when things got interesting.

The previous December, Benjamin Franklin had received an unusual packet in the mail. He was living in London, where among other things, he served as deputy postmaster of North America. To put it in 21st-century terms, someone inside the very top levels of England’s government had gone rogue and wanted Franklin to know what was secretly going on behind closed doors.

The packet contained about 20 letters privately sent to a top aide to the British prime minister by Thomas Hutchinson, the Massachusetts colony’s royal governor, and other local officials. Franklin couldn’t believe his eyes. The letters framed matters in a way that intentionally misled Parliament.

They also suggested Massachusetts’ colonial government should be overhauled to give the royal governor more power. Worse still, Hutchinson wrote that the colonists should never have the full rights in America that were enjoyed back in England, calling for “an abridgment of what are called English liberties.” Franklin forwarded the letters to Boston with clear instructions that they not be printed or publicized.

He added, however, that they could be quietly shared with Patriot leaders. However, those brilliantly conniving second cousins, John and Samuel Adams, made sure the correspondence reached The Boston Gazette. When the letters were published in June 1773, the public in New England reacted with the ferocity of a nuclear blast.

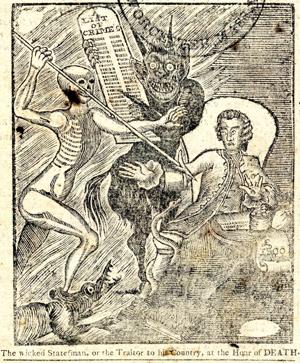

Hutchinson was burned in effigy on Boston Common. The outcry was equally intense when word reached the other side of the pond. From Beacon Hill to London’s fashionable salons, Britons and colonists alike speculated about which insider had leaked the letters.

One suspected source blamed another, even leading to a duel between two men. That was when Franklin said enough was enough. On Christmas Day 1773, he published a letter admitting that he had forwarded the letters to Boston.

Franklin was hauled before the Privy Council, royally chewed out, humiliated and fired from his lucrative deputy-postmaster gig. Back in Boston, the revelations from the letters helped stoke the anger that climaxed with the Boston Tea Party. You know what happened from there.

So, who was the 18th-century resister inside Britain’s government who actually leaked the letters? There’s a wide cast of possibilities. Several historians point a finger at Thomas Pownall, Hutchinson’s predecessor as royal governor. Others blame John Temple, another colonial official.

Temple claimed he knew the true culprit’s identity but refused to name him, since doing so “would prove the ruin of the guilty party.” Whoever they were, their secret went to the grave with them, but its effects are still felt today..

Politics

Holy Cow History | The leak in London that spilled the tea in Boston

In 1773, one unidentified official's disagreement with his boss, and his actions to inform Americans about it, played a big part in the buildup to the Revolutionary War.