If you haven't thought of or talked about Indian Non-Alignment in a while, you're not alone. Swapna Kona Nayudu, faculty member at Yale-NUS in Singapore, says it hardly ever comes up in her circles comprising historians, international-relations scholars, and lecturers, too. As early as 1945, India took one of its first steps towards defining the kind of country we wanted to be on the international stage.

Indian non-alignment was born as much out of pragmatic concerns as an anti-imperialist response in a world going into what came to be known as the Cold War. In her new book, 'The Nehru Years: An International History of Indian Non-alignment', Yale-NUS faculty member Swapna Kona Nayudu explains how Indian Non-Alignment arose from the very specific conditions India found itself in, in the 1940s: on the cusp of Independence, India chose not to side with the First World or the Soviet Bloc; neither capitalist thought, nor communist. And yet, Indian Non-Alignment was not a kind of neutrality, nor was it the same as the Non-Alignment Movement (NAM) At the Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), a New Delhi-based think tank where Kona-Nayudu got access to some archives of the Indian Armed Services in 2008, she followed her You write in the book how non-alignment is one of the first stands that India takes on an international stage as a soon-to-be independent nation.

What is the legacy of Indian non-alignment? We talk about strategic autonomy today–is that a kind of non-alignment for the present day? Legacy questions are really interesting because they are so fraught with tension. And the moment we talk about legacy, we (typically) talk about individuals. I love this question because it’s actually about the legacy of an idea.

Now, even when we look at non-alignment, it's very different under Nehru, under Indira Gandhi, under Rajiv Gandhi, till the time that we sort of almost stopped using the phrase at all. So if we're talking about non-alignment of the Nehru years, the world we live in is so different that it's hard to draw these sorts of historical links. Having said that, yes, I think that strategic autonomy would have been a subset of what non-alignment was.

What it was back in the day was much more expansive. And because of the needs of the day, because India was newly post-colonial, the political philosophy had to give us a toolkit and the toolkit had to include many things in it. So, it’s a much more an approach, which of course has its uses, but I think that to some extent it's a subset of the larger philosophical approach.

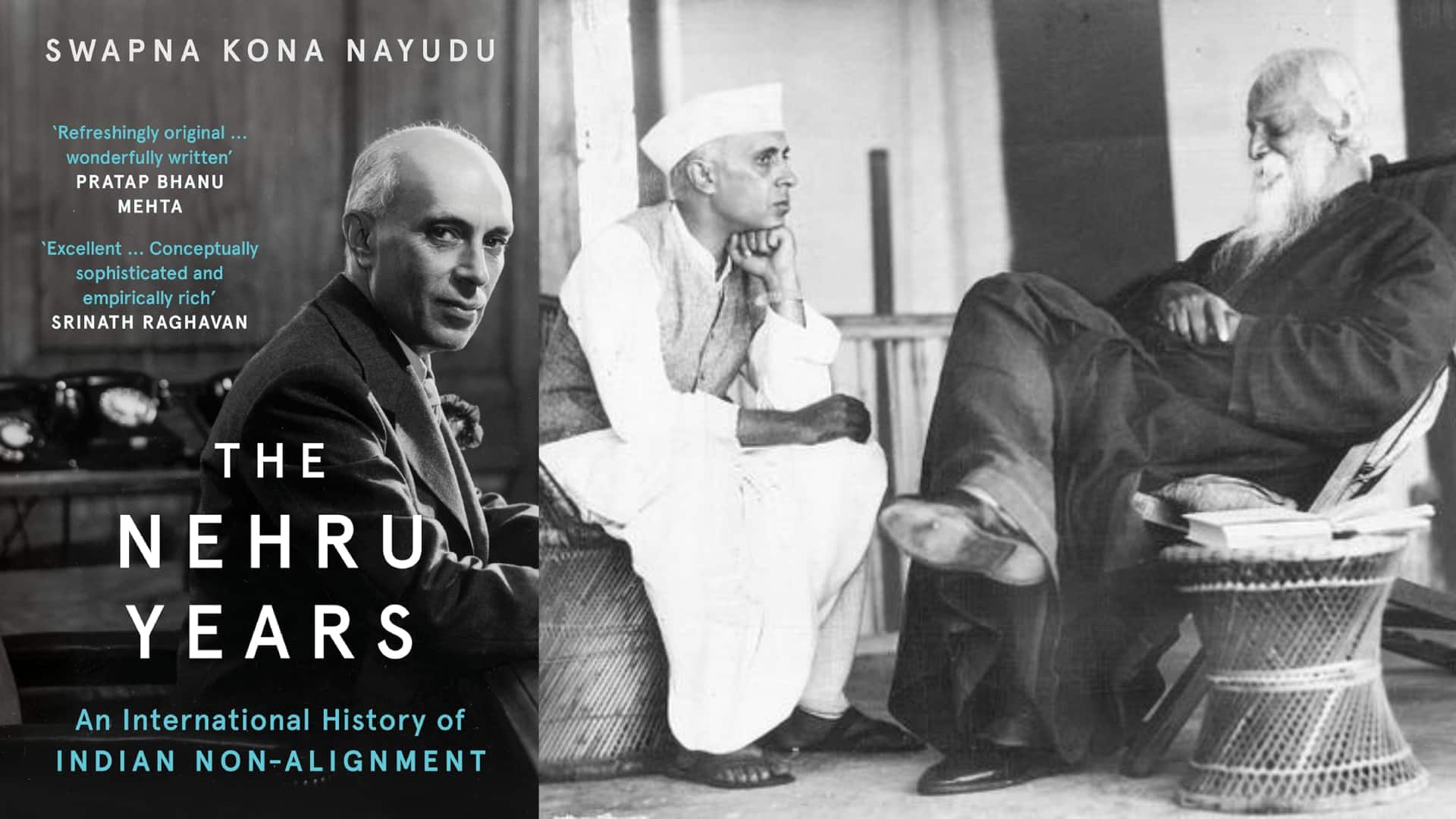

Then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru at the April 1955 Bandung Conference of 29 Asian and African countries, where a consensus was reached condemning 'colonialism in all of its manifestations. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons) Why do you say that strategic autonomy would be a part of non-alignment – what did non-alignment have that strategic autonomy perhaps is missing or has no need of today? Non-alignment also had various other aspects to it. For instance, an interest in nation states, nationalism, anti-colonialism, beyond geopolitics.

Now, obviously that is an idea very much of that time. It doesn’t have much of a place in today’s affairs, but that anti-colonialism drove a lot of other thinking, and a lot of questions about nation-making ethics, and world affairs of that time. There've been many other terms thrown around as well: Diversified dependence, multi alignment, strategic autonomy.

I think what people who have come up with these concepts are trying to do is, to some extent, use what we can from historical non-alignment. One could say that there's a legacy, but I think that in some ways it's such a different world and it's such a different utilitarian approach that to some extent non-alignment didn't have. Critics of non-alignment will say that was the reason, for instance, that India lost the Sino-Indian war: Because non-alignment was not tactical enough.

The idea with something like strategic autonomy is in fact to prevent that. So, to some extent, these are juxtaposed now. Which is why I'm saying that the legacy question is a bit fraught because, yes, there are some aspects to it and there's some similarities, but I think that those who are currently using these terms would be wary of implying a connection that's too strong.

Just so I understand this clearly: You’re saying the idea of the nation and who we are as a people was more important to non-alignment than it is now, in the age of strategic autonomy? Or is there a more utilitarian, maybe even economic, approach to who we deal with and how we deal with them and how much we get intertwined in world affairs under strategic autonomy? That's a very good question...

Just because we don't like what someone else's concept of the Indian nation is, doesn’t mean they are not conceptualizing. We have been part of this project from before independence. For 100 years.

Because in the 1920s, we have (Mahatma) Gandhi's arrival and everything taking off...

from the civil disobedience movement, we're 100 years away from that now. So, I would say that that process has been continual in India. It has never stopped.

The ideas that come from various camps might be pretty antithetical to each other, but they are very much ideas of what the Indian nation is, what India will look like as a power: as a rising power, as a middle power, as a great power . This idea of power projection has been quite important to all the various constituent ideological camps that drive this defining and redefining. So, the iterative process is there.

I think that how interested we are in questions of power versus questions of identity is what sets the debates apart from each other. In the book, you write: ‘Non-alignment is anti-imperial politics that predated and outlived the Cold War’. Could you break this sentence down for us? In line with the whitewashing of history worldwide, there's also this idea that superpower rivalry from ’45 to ’91 is what defines the rest of the world; either you are on this side or that side or neutral.

And I wanted to take an axe to that and say that this doesn't ring true for the Indian experience at all. The fact that the Cold War existed gave rise to a certain set of historic conditions that India responded to. The non-alignment thinking is born out of Indian anti-colonial nationalism, which in a sense, is a predecessor to (it began before) the Cold War.

And, in other forms, it has existed beyond the Cold War. India has shied away from pledging alliance, a formal alliance at least, with any great power. So there has been this sort of move to remain autonomous, I guess, even if we don't want to say non-aligned.

In the introduction to your book, you say that Indian non-alignment is worth looking into, not just as something that existed in the 20th century, but something that perhaps can also give us a sense of how India developed from the time it became an independent country. Could you give us an overview of some of the key arguments that you make in the book around non-alignment as an act of civil disobedience, what it tells us about Jawaharlal Nehru’s thought and independent India’s earliest engagements on the international stage? I'm glad that you picked up on that line where it says non-alignment is an act of civil disobedience. A large part of my interest in this subject was motivated by two factors: One, the anxiety that non-alignment is such a dormant idea now.

Like you flagged, most of us have not heard of it for a long time...

my first degree was in history and then I did international relations and I have a degree in international law as well, but I haven't come across this phrase in such a long time. Even while being steeped in those fields, one doesn't hear about it at all. So, where did it go? It's almost like it mysteriously sunk.

Now, a few years ago, there was a sort of revival of this, when a bunch of senior scholars decided to publish this paper called 'Non Alignment 2.0', which then became a book. It was like a manifesto talking about the revival of this idea.

But it was very much a policy document that was focused on what this could do for India in the sense of global affairs and India’s role strategically. The second motivation for me was that where I was coming across this nomenclature, was in the revival it has had in the larger world, in terms of discussions on the non-aligned movement (NAM), which, in my mind, was quite distinct from Indian non-alignment. But Indian non-alignment, and India having been a leader of non-alignment, meant that those two things were often confused with each other–even those who recognize these as distinct still often use them interchangeably.

Because there's this idea that India was non-aligned and India was a leader of the non-aligned movement, so those are pretty much the same. The more I started studying this, I realized that that was not true. And that it was in fact quite counterproductive to our understanding of Indian non-alignment, because as you will see in the book, Nehru particularly was quite reserved in his commitments to NAM.

Particularly because a lot of this stuff is happening in the 1940s, when India is on the cusp of independence. It starts happening even before India becomes independent, but also carries on right after India gains independence. So, of course, there’s a sense of not committing your resources too much in any one direction.

Because there aren't any resources to commit this way. These people are working with very little and what I guess in today's day and age, we would call social capital. It's Nehru’s personal stature, it’s the position his family has internationally—with his sister Vijay Lakshmi Pandit’s role in the UN General Assembly—and so on and so forth.

So, through the 1940, ’50s and ’60s, there is this idea that we don't want to commit to this movement, also being seen to spearhead it in any sort of way. Because once we thrust ourselves into this leadership position, then we're going to have to commit to a certain ideology. And again, I explain this in the book as well, because there is a reluctance to ideology on the whole as a concept—both camps, the First World and the Second World—there is the idea that the Third World cannot become a third bloc.

And so Indian non-alignment from the very start, at least in the Nehru years, is very much also defined by what it is not. The idea that it's not the non-aligned movement, the idea also that this is not a shared ideology. So that's two things.

The third thing is this idea that Indian non-alignment is not neutrality. The sort of questions about the ethical commitments that come through non-alignment as a political philosophy is very important to people who are thinking about these things, particularly Nehru. This idea of what it means to conduct yourself as a nation state ethically in world affairs obviously has roots in Gandhian thinking, which is why there's also a discussion of Gandhian politics in the book.

Also because of the Asia-Africa angle, it's quite interested in these concepts of the Third World, Global South , Asian solidarity, things that have more concretized names today, which were at the time quite diffuse concepts in the sense that were they coming together. There's also very deep cosmopolitanism. This idea that we need to be more fluid, there needs to be movement of ideas, that we need to live in a world that is quite cultural and intellectual.

Again, a lot of that comes from (Rabindranath) Tagore, which is why the big conceptual chapter that I was talking about is all Tagore and Gandhi as sources of thought for Nehru. I wanted to do a deeper dive on what transpired, to come up with this philosophy as opposed to seeing it as almost having pre-existed. When you read a lot of the writing from the time, you see the fact that if you don’t want to choose the Second World or the First World, you're (considered) non-aligned; it’s seen as neutrality.

I wanted to talk about how it's not quite as simple as that. It's not just not choosing either the capitalist mode or the communist mode, it’s more than that. It’s more about what could we be as a nation.

While there is a lot of general public interest in India's war history and border skirmishes, there's less interest in the peacekeeping missions. To be sure, there have been some books recently, like one by Major Rajpal Punia on the Indian peacekeeping force in Sierra Leone in the year 2000. But not many people today will remember the part India played in the Congo or in the Korean War.

Did this difference figure into your research and the book as well? UN peacekeeping versus border conflicts was such a big motivator for me to do the empirical work. One of the things that I wanted to do in order to reinforce this idea of India's commitment to worldmaking; not just nation-making for the Indian state, but worldmaking. It's not just a question of how India will approach the world, also a question of what sort of world will we live in.

If India is entering this world, what would that mean? I'm quite interested in these kinds of questions of what kind of world India wants to constitute. What I wanted to do is remove this factor of territoriality. To take that away and say: how does India behave when its territory is not at stake? And then the second chapter, which is the big one, in 1956 is about Europe and these other kinds of nationalisms that India is not so intimately connected with and doesn't know why it supports them.

As someone who's slightly historically trained, the Congo chapter was for me very interesting because no one had written about it. I have to credit Srinath Raghavan for giving me the idea that I should look at something in Africa. The idea with focusing on UN Peacekeeping and India's role in it, was to talk a little bit beyond parochial lines.

Conversations quickly descend into that space when we're talking about Pakistan or China and India's borders with those states. I wanted to move beyond that, but also not beyond that in a sense that we're only talking about India and South Asia. Political scientists go into questions of hegemony, what kind of role India plays in the neighborhood - there's a lot of very interesting work on those questions.

I was much more interested in the political philosophy that drives this foreign policy. And if I have to go into that, I have to move away from Pakistan and China because there's no way of actually understanding what someone wants India to be when we're always talking in terms of territorial competition. Also because a lot of the theoretical work that underpins this writing, is based on war.

My idea also is that with Pakistan through victory and with China through defeat, India's role is always tainted by war in the neighborhood. We're almost unable to escape those ways of thinking. India is so interested in its various wars, skirmishes, conflicts with Pakistan and so cagey about what happened in ’62 that a lot of any other discussion is not possible, particularly when it comes to the person and thought of Nehru.

Because whatever someone has to say that’s interesting or critical, stops when we reach ’62. Is it 1962 or even earlier, because in the book you mentioned that there is a certain radicalism that is attributed to Nehru in the pre independence years, which seems to have been sort of nullified or at least dimmed post-independence where his ideas are sort of almost taken as India speak rather than some sort of way of exercising agency in shaping what India will be. Yes, if we are going to discuss this thought, then let's try to do it in a slightly critical way, which is only possible when we move away from the neighborhood.

That was the idea with going into UN peacekeeping. Also, it makes sense because I was so interested in India's commitment to the UN. Indeed, this book is as much a history of the UN as it is a history of Indian foreign affairs.

And I think a lot of histories of the United Nations are so whitewashed that it was very important to me that we highlight these. How did you become interested in studying wars, and Indian non-alignment? I had a weird segue into academia. I worked around South Asia and then went into my PhD, which was with Sunil Khilnani, at King's College London.

I trained as a theoretical and historical interventionist on war. My main focus in all my scholarship since the PhD, or actually even before the PhD, because that's what I was doing when I was working with the Indian Army as well, is focusing on wars and what they meant for India. Also, I think more than as a military historian, I've been interested in the theory, the political thought behind it.

What kind of work did you do with the Army? It was with CLAWS, around 2008, with a director, (late) Brigadier Gurmeet Kanwal . He was very well respected and known for institution-building in a sense. His idea was that: Look, there's a bunch of young people who are now studying things theoretically and historically to do with the military that the military doesn't actually draw on.

And India's civil-military relations are set up in such a way that there's very little cross-movement between civilian life and military life. So, his idea was that we're losing out on all this expertise because we're not actually getting these people (civilian researchers) to work for us (the Armed Services) or to gain any insight from what they're doing. I was always sort of, in the background, working on peacekeeping.

I've been working on peacekeeping for over 15 years–collecting data, talking to people, etc. What I got (at CLAW) was a lot of exposure to how peacekeeping works: What does the military think about it, etcetera; a sense of what it means for the Indian Army to send people as (UN) Peacekeepers . I didn't know it at the time, but I think that it turned out to be quite formative in my PhD thesis, which is now this book.

.

Politics

'Nehru Years' author: Strategic autonomy would have been a subset of Indian non-alignment, but we live in a very different world today