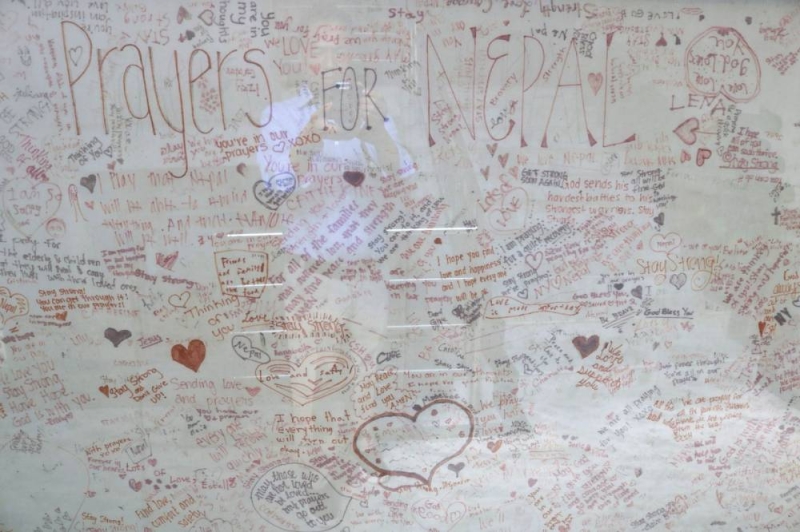

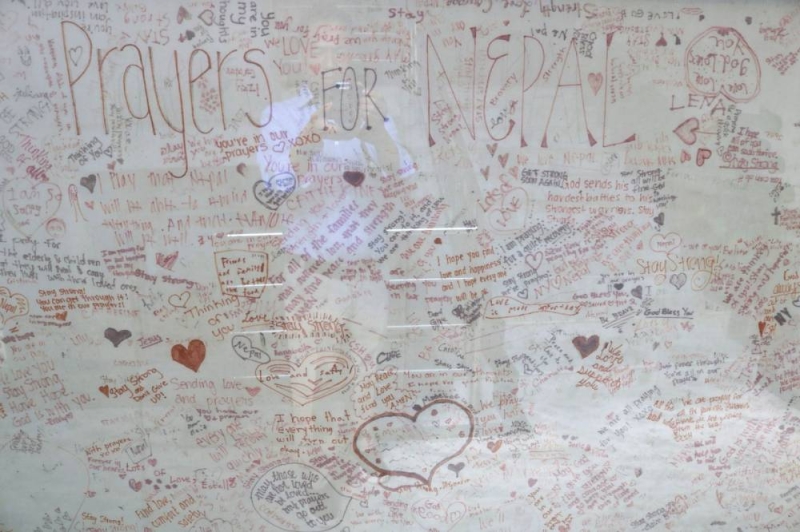

It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that when the earth shook on April 25, 2015, the lives of Nepalis changed forever. The 7.8-magnitude Gorkha Earthquake claimed more than 9,000 lives and displaced millions.

In the decade since, we've rebuilt homes and restored infrastructure-but the deeper cracks in our disaster preparedness systems remain alarmingly unaddressed. Bimala, 37, a mother from Gorkha, was five months pregnant when the quake struck. "I thought it was the end," she recalls.

Her home was destroyed, water sources dried up, and she had nowhere to go. She eventually gave birth at a temporary health post set up by Save the Children. "We survived, but even now, I live in fear of what comes next.

" Nepal sits along the active boundary of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates, making it the 11th most earthquake-prone country in the world. And yet, despite this well-known risk, we remain dangerously underprepared. Nepal has introduced important policies, such as the Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act and the National Disaster Response Framework.

But implementation at the local level remains weak. Community disaster plans often exist only on paper. Local governments-our first line of defense-still lack the capacity and support to make the quick decisions required by law.

We've also seen that these plans must move closer to the people-especially children from marginalised backgrounds-whose voices are too often excluded, with little or no reference to their lived experiences. It is well known that during disasters, children face heightened risks: trafficking, interrupted education, poor sanitation and long-term psychological trauma. Yet our response models still tend to follow a one-size-fits-all approach, often overlooking the specific needs of children, women and underrepresented groups such as LGBTQI+ individuals and persons with disabilities.

There's no denying that we remain at risk, and the consequences of this gap are stark. In November 2023, a 6.4-magnitude earthquake struck Jajarkot, killing 154 people and flattening more than 60,000 homes.

So, when the next big earthquake hits, will we be ready? Our consultations with survivors of the Gorkha Earthquake suggest otherwise. Key informant interviews with more than a dozen individuals most affected by the disaster reveal a sobering truth: communities are still fragile. A critical review of our humanitarian response systems shows that our efforts remain largely reactive-and the most vulnerable, especially children, are often an afterthought.

When the Gorkha Earthquake hit, Save the Children Nepal was among the first responders. We reached over 580,000 people, including 352,000 children, with life-saving support: temporary shelters, clean water and sanitation services, and essential non-food items. We set up temporary learning centres, offered psychosocial support and helped children regain a sense of normalcy amid the chaos.

The destruction was immense: nearly 30,000 classrooms across 8,304 schools and almost 1,000 health facilities were destroyed or damaged. A decade later, we continue to work alongside local governments to ensure that preparedness is not just about having plans-it's about centering people. Through capacity-building of local emergency operations centres, local disaster management committees and school-based disaster risk reduction programmes, we are strengthening communities' ability to anticipate, respond to and recover from disasters.

At the heart of our work is child protection-ensuring that children's needs are not only met after a disaster but anticipated before it strikes. One thing has become clearer over the past 10 years: humanitarian action must be localised. And this doesn't just mean shifting resources-it means sharing them with those on the frontlines, especially local governments.

In line with this, we've introduced a Combined Relief Approach-an innovative model that integrates the capacity of local governments with Save the Children's humanitarian response. Beyond immediate relief, this model promotes government ownership, transparency and shared action. It enables joint resource mobilisation, pooled expertise and coordinated responses from the outset.

In doing so, it strengthens local governments' ability to lead in future crises and ensures that the voices of children are centered in both pre- and post-disaster actions. Similarly, inclusivity and diversity should not be peripheral during humanitarian crises, they must be central to how we deliver impact. Guided by this belief, Save the Children introduced "Rainbow Kits"-dignity kits specifically designed for transgender individuals affected by disasters.

This first-of-its-kind initiative reflects our commitment to ensuring that no one is left behind. Traditionally, humanitarian kits have followed a binary framework, often overlooking the distinct needs of gender-diverse communities. Rainbow Kits break this mold by providing essential hygiene items that support dignity and well-being for transgender individuals, particularly in emergency settings.

But this is more than just a supply kit- it's about recognising identity, affirming rights and reimagining what equity in crisis response truly looks like. These tailored kits promote inclusion and ensure that all identities are respected, regardless of sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, or sex characteristics (SOGIESC), setting a new standard for dignified, people-centered humanitarian action. Still, I must say-though we've made progress, it's not enough.

We must intentionally partner with local governments and collaborate with the children and communities we work with-and for. Global humanitarian funding may be shrinking, but for a country as disaster-prone as ours, preparedness is not a luxury-it is a necessity. Investing in local systems, community-led solutions and child-centered disaster planning must become national priorities.

Because when disaster strikes, children-and those who are most marginalised-suffer the most. And they deserve better..

Politics

Ten years since the Gorkha Earthquake: Nepal is still not fully prepared

It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that when the earth shook on April 25, 2015, the lives of Nepalis changed forever. The 7.8-magnitude Gorkha Earthquake claimed more than...