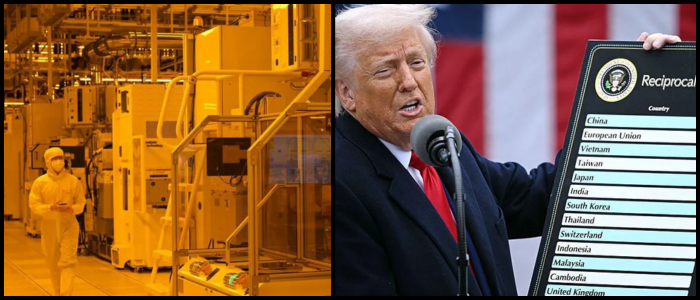

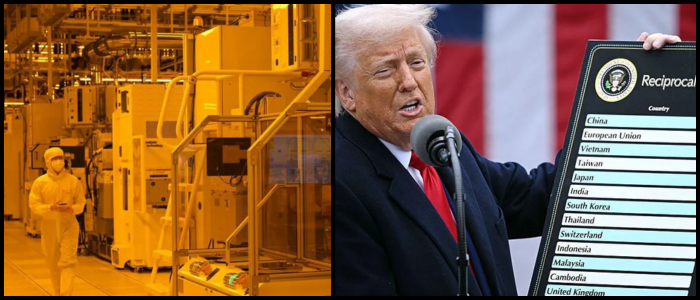

As the 90-day tariffs pause is scheduled to end on 9 July, businesses and countries are scrambling to react. The US government, Trump said, will begin sending out letters on 1 August to notify affected businesses that the government will collect a 10% tariff on products from China that are listed in a frequently updated book of specifications. That figure could vary between 10% and as much as 70%, but he declined to say which countries would be targeted.

Semiconductors have so far been spared, but the threat of these tariffs remains, making it hard for companies like GlobalFoundries — which counts major players like AMD, Broadcom and Qualcomm as its customers — to know what to plan for. Little is known about the company, which operates in several nations in Asia, such as India and South Korea and recently announced it would be investing $16 billion to keep pace with the exploding AI hardware market.

Further complicating the situation is a report that the US is planning AI chip export bans on Malaysia and Thailand. These uncertainties have led companies to mull relocating operations to the US and to ratchet up their buffers and inventories to handle disruption.

Winners, Losers and Supply Chain Reactions

Trump's announcements of tariffs earlier this year included steep rates on more than one Asian economy — of 24% for Japan, 25% for South Korea and 46% for Vietnam. Many of these had been reduced to 10 per cent under a temporary pause, but higher rates could return right after 9 July.

Malaysia has warned that tariffs could hurt industries like textiles, plastics and rubber. Singapore, which is under a free trade agreement with the US, will still have to pay the 10% tax. Comments by Singapore's prime minister suggest frustration, as he says that such moves are not something reasonable people do, and "certainly not something that friends do." Southeast Asia represented 7.2% of the world's G.D.P. last year, and the inflationary costs of tariffs could be lasting.

Among Southeast Asia nations, the US has only succeeded in striking a deal with Vietnam, whose exports are subject to a 20% tariff while US products enter duty-free. Japan and South Korea are also still in negotiations, but Trump has threatened Japan with tariffs of as much as 35%.

Sectors such as automotive and textiles could be hardest hit. Mazda, for example, is finding it hard to adjust because of the months it takes to find new parts suppliers. Even Australia, a central American security partner, has made the case for a tariff rate of zero. Those countries, including Indonesia and Thailand, have pledged to buy more from the United States, while Cambodia, which has little leverage to negotiate, faces an onerous 49 per cent tariff.

Professor Pushan Dutt makes the point that Asian economies are highly plugged into the global supply chain and depend on both the US and China. The stakes could be high for export-dependent countries like Singapore and Vietnam, though India may fare better because of strong domestic demand.

Trade Flows Globally and Changing Order

After Trump was initially elected, countries such as Singapore and Malaysia doubled down on investment in driver sectors such as chip manufacturing and data centres, bracing for a world of "friend-shoring" and "China + 1" strategies to ensure ongoing access to the US market.

Despite the trade tensions, the United States is still a critical consumer market for many Asian companies. But escalating tariffs are prompting American companies that have become deeply entangled in Asia — ones that make clothing and sell shoes, for instance — to reconsider their reliance on the region. Brands including Nike may now have to transfer additional expenses to consumers.

Foreign inflows will also adjust. Low-tariff countries, like the Philippines, Singapore and Malaysia, may see more investment while others, like Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, could fall behind. Firms are hunting for ethnic niches in Europe, the Middle East and Latin America.

Chipmakers are now opting for regionalisation over globalisation, according to Mr. Tan from GlobalFoundries, searching for secure locations to source from, even at a premium. As the U.S. becomes an unpredictable trading partner, Asia is building new alliances and opening up.

This change offers China the chance to augment its position in global trade. To date, only three tariff deals have been agreed: with Vietnam, the UK and China. Unless other countries follow and fast, Asian economies might have to turn to new strategies to remain competitive.

Ultimately, the sustained changes in tariffs may reshape the global economic map. Still, "Bow to the ruler, then you're free to go," as Prof. Dutt puts it.

Business

Trump Tariffs Reshape Asia's Business Future

Tan Yew Kong, in charge of operations for GlobalFoundries in Singapore, likens his company to a tailor shop, tweaking semiconductors to client specifications. "We give you the fabric, we give you the cufflinks, all you do is tell us what you like and we'll make it," he says. Today, such customisation extends to planning for US President Donald Trump's ever-changing tariff policies.