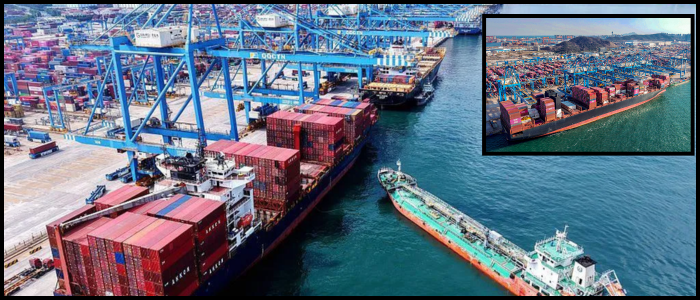

Australia is throwing its weight behind this site, furnishing Iluka Resources with an A$1.65 billion (US$1 billion) government advance to mine corpuscular imbued sands there and refine these things. The objective: develop an alternate supply chain from China that controls rare earth production for years.

This Is How The Market Was Moulded by China's Grip

The US sense of urgency increased after the supply was targeted by former President Donald Trump in his trade battles with Beijing. Manufacturers went scurrying after China cut off rare earth exports, a major weapon in tariff negotiations. Ford even shut down its production of the Explorer SUV in Chicago for a week, laying the blame on issues with rare earth supplies.

While Beijing allowed a relaxation in the policy, the episode illustrated how dependent certain industries had become on these materials. Today, China accounts for more than 50 percent of global supplies of a broad range of rare earth minerals and controls approximately 90 percent of the processing and refining capacity. China accounts for 80-90 percent of US imports of rare earths, and over 98 per cent of the European Union's supply.

Dan McGrath, head of rare earths at Iluka, says: China deliberately undertook to control the market in support of its own manufacturing and defence capabilities.

Iluka's Accidental Advantage

Iluka has been mining zircon there and the titanium dioxide it needs for producing ceramic tiles, paints and plastics in Australia for decades. These operations produce byproduct dysprosium and terbium rare earth elements. Australia's government has been stockpiling these byproducts for more than a decade, and the resulting stash is now worth over A$650 million.

But mining those minerals was great work, cutting a far simpler job than the challenging chemical separation needed for refining. They are chemically identical in some ways, so they separate easily. You will also have to deal with radioactive waste, explains Curtin University metallurgy chair Jacques Eksteen.

Oxygen Enriched Air: The Refining Challenge and Government Support

Iluka's refinery is expected to be up and running within two years. McGrath says the project wouldn't work without the government's billion-dollar loan. By 2030, Iluka aims to meet a significant portion of Western demand for rare earths, which would come as an alternative to China's dominance of the market.

Since automakers and tech companies need to plan years ahead, Iluka is already fielding requests for supplies in the future. Her UKIP leaflet states that, as rare earths are used in both clean energy technology and modern defence equipment, a UK-SR "could be termed a UK Critical National Infrastructure project.

Strategic, But Not Without Risks

However, Australia's Resources Minister Madeleine King said the world market for rare earths is not really open because one dominant supplier can control prices and production at will. In her opinion, "we will either do nothing or stand up to face the challenge of creating an internationally competitive industry".

But environmental concerns must be overcome to drive the industry forward. Despite this, China has already been left with radioactive waste and chemical by-products polluting many of its waterways due to poorly regulated processing over the past several decades. In Australia, there are tougher environmental frameworks, but refining involves similar emissions from leaching, thermal cracking and waste management.

"There is no metals industry that is 100 percent green," Eksteen says. "[But] here in Australia, we have the systems to do it properly.

Positioning for the Long Game

China was accused by the European Union of using its control of rare earths supplies as a political weapon to try to further weaken competitors. If suppliers are stable today, the fact that they might not be tomorrow puts even more pressure on manufacturers to seek alternative supply.

Indeed, with deep stores of minerals, strong rule of law and no doubt some help from the government, Australia could emerge as a legitimate alternative source for rare earths in a world that continues to demand supply chains that are cleaner and more transparent — perhaps most critically: free of China.

Business

Australia's $1 Billion Plan to Break China's Rare Earth Grip

Eneabba, a few hills sprinkled over the flat desert land, is three hours north of Perth, in Western Australia. Three hours north of Perth, you will find Eneabba. Beneath its barren surface lies an enormous open pit — not of regular soil, but a million-ton stockpile of rare earth minerals vital for electric vehicles, wind turbines and defence systems.