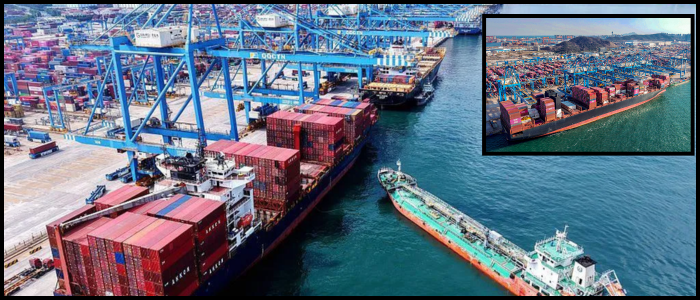

These 17 elements are vital for manufacturing electric motors, sensors, and high-tech components employed across various sectors. The growing scarcity has stimulated renewed discussion on the matter, with rare earths among the top items on the agenda for this week's trade negotiations in Lancaster House, London. Despite Chinese President Xi Jinping's vow, both administration experts and business representatives are sceptical of a quick or long-lasting resolution to the crisis. According to Gracelin Baskaran of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, U.S. companies only have two to three months' supply of rare earths.

"Industry could not manufacture," she predicted if there was no agreement. The American auto business has already been severely impacted. The Chicago Ford factory had recently closed down, and other manufacturers were forecast to follow suit this year. "It's not only EVs," one source said. "We have compounds in everything. On a scale from windshield wipers to seat belts, that's how the shortage looks like." Licenses that give major automakers like GM, Ford, and Stellantis permission to export rare earths out of China have already been issued, but it is only for up to 6 months. U.S. officials, on the other hand, are pressing for longer-term solutions to avoid production bottlenecks.

As per specialists like Roderick Eggert of the Colorado School of Mines and the difficulty of discovering viable alternatives, he said, "every motor model is somehow less efficient than the one found" in rare earths. While the nation is creating new domestic processing facilities, these endeavours are still years distant. Rare earths, despite their name, are not particularly hard to come by—the knowledge and infrastructure needed to refine them are heavily concentrated within China. "We should have seen this," Baskaran said. "We should have started this 15 years ago."

Business

Rare Earth Crisis Looms as U.S.-China Trade Talks Hang in the Balance

The future of key industries is hanging on the balance as U.S. and Chinese trade officials meet in London. A shortfall in rare-earth minerals, used to manufacture nearly everything from smartphones to automobiles, has led to a risk of major supply disruptions. Auto experts cautioned that the sector could encounter a considerably more serious crisis than the pandemic-era chip shortage soon. China, which handles almost 92% of the global rare earth processing, imposed a new licensing rule in April that dampened worldwide exports, including those to the United States.