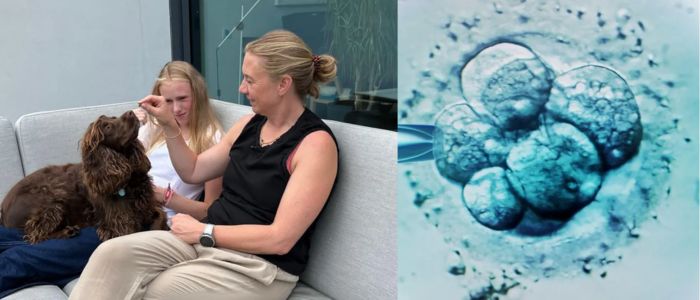

South Korea's fertility clinics are in high demand even as the country records some of the world's lowest birth rates. Fertility treatments increased nearly 50 per cent from 2018 to 2022, with 200,000 procedures performed. One in six babies born last year in Seoul was conceived through fertility treatment alone.

This increase is a noteworthy departure in the attitude of the younger generation toward family planning. Many of them are deciding to take health and fertility into their own hands. There are more single women freezing their eggs, and couples are more open to IVF when they struggle to conceive naturally. For people in today's generation, planning is crucial, while in past generations, having a conception was considered something uncertain.

A Shift in Family Choices

South Korea's government has long sought to cope with demographic challenges brought on by an ageing population and declining births. Today, one in five of the people in the country is over 65. In the intervening years, South Korea has continued to set the world record for lowest fertility rate — 0.98 babies per woman in 2018 fell to 0.84 in 2020 and remained in free-fall at 0.72 in 2023. Should this persist, the nation of some 50 million people could shrink by half over the next 60 years.

But, there is one small bit of good news. In 2024, it showed a slight increase of 0.75, which is South Korea's first increase in nine years. Although it remains below the global average of 2.2, experts said this could be a meaningful shift. That slight increase could portend a longer-term change, depending on how younger people continue to feel about marriage and parenthood, said Seulki Choi, a professor at the Korea Development Institute's School of Public Policy and Management.

Delayed but Not Abandoned Dreams

For Park Soo-in and many others in South Korea, the idea of having children wasn't a possibility in their early years because of demanding jobs and lifestyle pressures. At 35, Park remembers being in the advertising industry and frequently working until 4:00 AM. "It wasn't even an option that was in the realm of possibility for me to consider," she said.

That changed when she married and switched to a job with more favourable hours. Her friends began having children, and her husband was supportive and hands-on, which helped to lend her a feeling of confidence. Having encountered difficulty in trying for their first child naturally, the couple decided to undergo fertility treatment, a choice that more South Koreans are making these days. More than $2 billion is the worth of the fertility industry by 2030, according to estimates by experts.

These trends indicate that many men and women still want to start families but are encountering obstacles, experts said. Women adapted to social norms that require them to take care of children. Young couples remained discouraged by long working hours and expensive education from having children.

More Than Half of South Koreans Want Kids; Most Can't Afford Them, U.N. Report Shows. South Korean women have their first child at age 33.6 on average, one of the highest rates in the world. Yes, is the answer that Park gives -- "I wonder if I would have been a lot better if I had started slightly earlier. "But honestly, the time is just right now."

Kim Mi-ae also had a similar experience, saving for years for her marriage and for even more time for having a baby. "Young people study, prepare to find jobs and create lives. By the time they're ready to settle down, it's late very frequently," she said. "And the longer you wait, the worse it is — physically and emotionally."

Health

Fertility Clinics Rise as Birth Rate Hits Record Low

When Kim Mi-ae started her second round of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) late last year, she braced herself for another painful, expensive struggle after a friend in her mother's group faced the difficulty of having her first child through the same procedure three years earlier. But suddenly she was shocked by the long waiting times at the fertility clinic. "When I went in January, it felt as if every single person in the room had made a New Year's resolution to have a baby! It took more than three hours, in cheek-by-jowl conditions, even though I had a reservation," the 36-year-old from Seoul said.