The trauma is evident in Uttawar, a village in Haryana's Mewat region. Growing up as a child of a man whose entire village was dragged to prison in 1976, Mohammad Deenu's most vivid recollection occurred on a November night of that year, when security forces surrounded the village, forcing all fertile men into its main square. As others ran to the jungle or hid in wells, Deenu remained. He was sent for sterilisation, along with 14 others. "We saved this village by our sacrifice," Deenu said, explaining that his choice saved others from more severe consequences.

The Repercussions of a National Policy

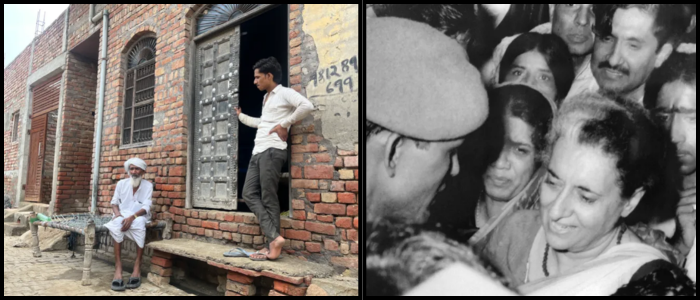

In 1952, India had started a national family planning programme, which under the Emergency became coercive. The government at the time, led by Prime Minister indra gandhi, imposed quotas on sterilisation for bureaucrats, delayed salaries and ceased irrigation to noncompliant villages. Fueled by financial incentives from the global community, the effort picked up steam.

Muslim-dominated villages such as Uttawar were more affected as they tended to have a relatively higher birth rate. Mohammad Noor, Abdullah's father, also fled in a raid before eventually being picked up and beaten before being freed. Houses were flattened and food made inedible with sand mixed in with flour. The emotional and social costs were staggering. For years, men from Uttawar were turned down in marriage proposals, and many never recovered from psychological stigma.

Abdul Rehman, the head of the village, defied pressure to surrender men to the authorities by stating, "I will not give dogs from my area and you are asking for humans from me." Armbruster's stand notwithstanding, the village was hit hard.

A Dark Cloud Over Democracy That Still Hangs

While the Emergency officially ended in March 1977, its legacy lives on. Experts say the shutting down of rights and the collapsing of institutions in that period laid the foundation for authoritarian impulses in modern India. The swift collapse of democratic checks under powerful executive control — not to mention the capacity of India's principal opposition party to turn a blind eye to it —"has to been seen to be believed," as the political analyst Asim Ali pointed out. Indra Gandhi went on to lose the following elections, but the ghost of the emergency-era governance linger.

Since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office in 2014, some analysts and civil rights activists see the return of fear and censorship. While there is no official emergency in force, critics contend that the law exists to be used alongside the state of repression. Press freedoms have shrunk, dissidents have been imprisoned, and institutional independence is under pressure.

The memories are still on Deenu's mind. Transported to the camp, all he could think about was his pregnant wife Saleema. He was sterilised in Palwal after eight days. One month later, Saleema had their only child. Today, Deenu lives with grandchildren and great-grandchildren, proud of his family, and proud of the role he thinks, with more equivocation than boastfulness, he played in keeping his village whole.

Sterilisation was a curse that has haunted Uttawar every single night since," he said." "But we endured. Seven generations later and I'm still here to tell the tale."

Politics

India's Forced Sterilisation: A Village Remembers

On June 25, 1975, India stepped into one of its most oppressive periods of democratic history — Emergency. Civil liberties were curtailed, the press was censored, and political rivals imprisoned without trial. One of the most traumatising policies was the forced sterilisation campaign, more than 8 million men (6 million in 1976 alone) underwent vasectomies under pressure. Close to 2,000 lives were lost to botched procedures.